Born of Forest and Fire: The Adirondack Park Turns 133

The remarkable origin story of the Adirondack Park, born on May 20, 1892.

Mount Marcy in the Adirondack High Peaks region.

On May 20, 1892, something unprecedented happened in the Empire State: New York drew a line around a patch of rugged wilderness—bigger than Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Glacier combined—and called it protected.

1891 map of proposed Adirondack "blue line.” Courtesy NYS DEC.

Thus, the Adirondack Park was born. But this wasn’t some tidy act of conservation, served with tea and crumpets in Albany. No, the story of the Adirondack Park is a tale of loggers and legislators, fires and fortunes, mountain men and millionaires. And it all started with a wild idea: maybe, just maybe, forests mattered.

So grab your bug spray and let’s time travel to the park's roots, where we now paddle, hike, and hammock.

A land untamed.

Before there was a park, there was just wilderness—dense, ancient forests that stretched beyond imagination. The Adirondacks were remote, rugged, and largely uninhabited by white settlers until the 19th century. Moose outnumbered men. Trees towered. The land seemed inexhaustible.

As Connor Williams, the historian at Great Camp Sagamore, told us recently on the ADK Talks podcast, “If you think about the beginning of American history, people simply did not go into the woods. The woods were a scary place that separated towns.”

Blue Mountain Lake in the Central Adirondacks.

But by the mid-1800s, the Industrial Revolution had arrived with a steam engine’s roar. Railroads opened up access to the interior, and with that came loggers, miners, and entrepreneurs thirsty for timber and ore.

Once viewed as endless, the forests were being chewed to stumps by sawmills and scorched by fires set to clear land for fast profits.

The rivers—especially the mighty Hudson—began to suffer. Erosion clouded the water, and spring floods worsened as the forest canopy disappeared. By the 1870s, New Yorkers faced two unsettling problems: downstate cities were running out of clean water, and upstate landscapes were unraveling.

Cue the heroes of our story: conservationists, sportspeople, and a few far-seeing politicians.

Voices in the wilderness.

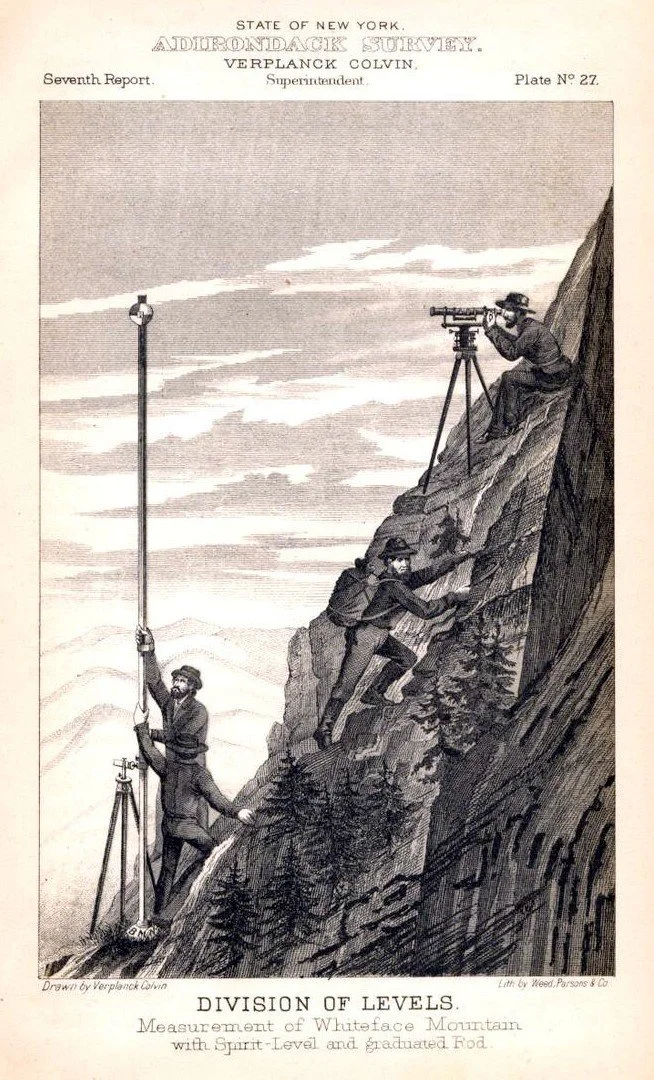

One of the loudest advocates for saving the Adirondacks was Verplanck Colvin, a land surveyor with the spirit of an explorer. Armed with a compass, alidade, and stubbornness, Colvin trekked deep into the High Peaks to chart the land’s topography—and its demise.

Measurement of Whiteface Mountain with Spirit-Level and graduated Rod", drawn by Verplanck Colvin, published in the Seventh Report of the Adirondack Survey, 1881

In detailed reports to the state, Colvin argued that preserving the forests wasn’t just about beauty—it was about survival. If you destroyed the watersheds of the Adirondacks, you jeopardized New York City’s water supply and upstate farming alike.

Meanwhile, writers like Seneca Ray Stoddard, a photographer and travel enthusiast, published guidebooks that romanticized the wilderness and showed it off to urbanites.

The Adirondacks became fashionable: a place to camp, canoe, and breathe clean pine-scented air. The rich began building “Great Camps”—rustic, oversized log mansions—while the middle class rode trains north to sleep under stars.

The pressure mounted: preserve this place before it vanished.

Albany’s really big Idea.

On May 20, 1892, New York’s legislature and Governor Roswell P. Flower made it official: They passed the legislation creating Adirondack Park, encompassing 2.8 million acres of public and private land. That mix made it unique then and still does today.

Lake Placid in the Tri-Lakes and High Peaks region.

The Park is unlike a national park, where the government owns every tree. Instead, it’s a patchwork where wilderness and working towns coexist, not always easily.

But the real game-changer came in 1894, when voters approved an amendment to the state constitution declaring that the Forest Preserve lands within the Park must be "forever wild." That’s not poetic hyperbole. That’s the law. Those two words—forever wild—meant no more logging, no more development, no more selling off lands to the highest bidder.

The forests, finally, had guardians.

The Park grows up.

Since 1892, the Park has evolved, expanded, and sometimes clashed with itself. Local communities sometimes feel squeezed by state regulations, while environmentalists have fought to strengthen protections. Still, the Park has managed to balance people and nature like few places on Earth.

Boat parade on Lake Champlain near Port Henry.

Today, it sprawls across over 6 million acres, making it the largest publicly protected area in the contiguous United States. That’s three times the size of Yellowstone. It’s larger than the state of New Jersey.

It’s worth noting that not all of the Adirondack Park is “forever wild.” About half of the Park is private land—home to small towns, working forests, resorts, backwoods camps, and year-round communities.

The rest, around 3 million acres, is public Forest Preserve, protected by that ironclad constitutional clause. That’s where the “forever wild” rules apply: no logging, no lease, no sale, and no motorized access (with some exceptions).

And yet, you’ll still find villages, general stores, ski hills, and one-lane bridges alongside bald eagles, bogs, and boreal forest.

The result? A unique checkerboard of public and private land where wild nature, recreation, and human life coexist—sometimes smoothly, sometimes with a few splinters.

The Milky Way reflected in Putnam Pond near Ticonderoga.

Where else can you climb a 4,000-foot peak in the morning and catch live music in a lakeside town that evening?

A living legacy.

Standing on a mountaintop like Cascade or Blue, it’s easy to think the Adirondacks are eternal. But this place—this idea—was born of crisis, compromise, and courage.

On May 20th, raise a toast to those with the guts to say “no” to short-term gain and “yes” to long-term wildness. The Park’s creation wasn’t just a legislative footnote. It was a turning point in American conservation, a beacon for how humans and nature might share space without destroying each other.

So whether you're paddling the St. Regis Canoe Area, backpacking through the Dix Range, or just sipping coffee on a porch in Tupper Lake, remember: this didn’t happen by accident. The Adirondack Park was made—intentionally, boldly, and perhaps most importantly—for all of us.

Happy Birthday, Adirondack Park. Here’s to another century of staying forever wild.

Dive Deeper

Your Adirondack Starter Library

Whether you’re sipping coffee on the porch of your camp or dreaming of your next trip up Route 73, here’s a list of essential reads to deepen your love of the Park. No footnotes, no heavy lifting—just great storytelling rooted in the Adirondacks' woods, water, and wild heart.

The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness, Paul Schneider

A vivid, sweeping history that reads like an adventure novel. You’ll meet surveyors, loggers, philosophers, and preservationists—plus the mountains, rising up like main characters.

Contested Terrain, by Philip G. Terrie

Smart and very readable, this one tackles the ongoing tug-of-war between people and preservation in the Park. It is great for context, especially about land use and Indigenous history.

Woodswoman, Anne LaBastille

A trailblazing woman builds her own cabin on a remote Adirondack lake and lives off-grid. Equal parts memoir, survival tale, and wilderness love letter.

A Wild Idea, Brad Edmondson

Behind-the-scenes stories of how the Adirondack Park Agency reshaped land conservation in New York. Surprisingly dramatic, with real stakes and strong characters.

Adirondack Tales, W.H.H. Murray

Published in 1869, this book kicked off Adirondack tourism. Charming, funny, and a little wild—it’s the original guidebook for city folks heading into the woods. Not easy to find.

BONUS PICK: Adirondack Life magazine

Before blogs and Instagram reels, Adirondack Life was how we knew what was happening in the Park—who was fishing what river, which barn was getting restored, and where the best backroad foliage could be found. It’s still the region’s best storyteller, in glossy pages or online.

Tip from a subscriber: Their archive issues are a gold mine for history buffs, photographers, and curious campers alike.